What is Resilience?

It has been called the great puzzle of human nature.

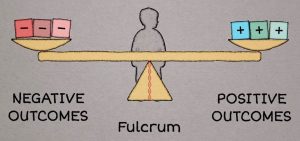

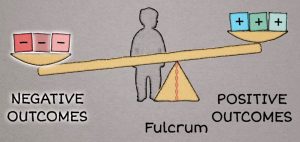

Is it something some people have and others do not? Is it something you can learn? Some research on resilience talks about genetics and a predisposition towards resilience. Here are diagrams of a seesaw with a fulcrum to illustrate this. Your life experiences and genetic predispositions sets this fulcrum to make your seesaw go up or down more easily. Adverse childhood experiences make moving the fulcrum more challenging. It can even make resilience out of reach for some people.

However, it is people who have had the most adverse life experiences and somehow have overcome them that inspire us the most. Who are these people and what did they do? The answer to these questions can help us understand resilience.

Resilient people possess three characteristics: a staunch acceptance of reality; a deep belief that life is meaningful; and an uncanny ability to improvise. You can bounce back from hardship with just one or two of these qualities, but you will only be truly resilient with all three.

Viktor Frankl was preoccupied with survivorship/resilience during his dehumanizing, life threatening experiences in concentration camps in Nazi Germany. He later traced the roots of his resilience to a sense of purpose and the acquisition of meaning. He then expanded meaning into three dimensions: purpose, mastery and autonomy. He wrote about in his famous book, “Man’s Search For Meaning”.

Other core characteristics of resilient people include the ability to form strong attachments to others and the possession of an inner psychological space that protects them from intrusion or abuse.

“More than education, more than experience, more than training, a person’s level of resilience will determine who succeeds and who fails. That’s true in the cancer ward, it’s true in the Olympics, and it’s true in the boardroom,” says Dean Becker, the president and CEO of Adaptiv Learning Systems, quoting from Diane Coutu in her Harvard Review Article, “How Resilience Works.”

So how can we train ourselves to become more resilient?

Realism versus optimism is key to resilience. Do I truly understand and accept the reality of my situation? It’s an important question to ask since we often slip into denial as a coping mechanism when facing difficult life experiences. Can I form meaningful relationships while preserving my own boundaries? Can I find a greater meaning even in the most wrenching circumstances or trust that it will become clear later? Can I improvise and dig a tunnel even if I only have a spoon – like one of the famous concentration camp escapes in Nazi Germany?

When I touch into my own sense of resilience I find two different varieties. One of them I will call the bulldozer. She will bulldoze her way out of a situation — head down, full steam ahead. The other one is softer and requires that I slowly sink into myself. What I find there is a kind of confidence and reassurance that I can handle whatever I am facing. This one I will name Helene, after my grandmother.

My Nanny Helene, as I called her, was the great love of my early life, and she loved me back. I was her first granddaughter and she adored me. It is an amazing feeling to be adored and I am sure this contributes to resilience, although I do not find it mentioned in the literature. My grandmother was a great dreamer and she always seemed to make her dreams come true, whether it was creating a successful restaurant in Washington D.C. or moving in the great social circles of the city. At a time in the 1950’s when many women spent hours putting on make up, doing their hair and dressing to perfection before leaving the house, my grandmother stuffed her dyed blond hair under a cashmere beret. A hat pin was the last thing she needed to keep the beret on her head while she rushed around the city — a career woman before her time.

She compensated for my grandfather’s dementia and devised constructs, as resilient people do, to make meaning out of suffering. With only one breast from a mastectomy, she bought her bras from a dismal medical supply shop. For her resilience was a reflex, a way of facing and understanding the world and building a bridge from a present day hardship to a fuller life in the future.

Resilient people face reality with determination, make meaning of hardship instead of crying out in despair, and improvise solutions from thin air. This describes my grandmother. I inherited some of these qualities from her, along with two of her hat pins. And here they are.

Acknowledgement: I drew heavily on the work of Diane Coutu, and her Harvard Review and her article, “How Resilience Works.”